I’m not sure when it happened, but sometime in the last fifteen to twenty years I began to feel it. It was a tingling anxiety and tension that began in my gut and kept growing until I was finally aware of it. It told me that, where I had previously stood firm on my interpretation of the world around me, I was now less sure about what was true than I had been before. Perhaps this was more due to the decline of youthful hubris than to any other factor, but it seemed that the more I dug, the more research I did, the less sure I was of many issues. For some questions, a quick Google search was enough to lay them to rest, while for others, the same search turned into a twisted maze of rabbit trails that seemed to lead nowhere but to confusion and uncertainty.

Nearly ten years ago I was asked to write an article on climate change for a Mennonite periodical. Before I began writing, I spent several weeks reading books and doing online research. I was finally able to write the article, but in some ways I was less certain about climate change than I was before I wrote it. I didn’t want to cherry-pick sources that only confirmed my previously held biases, so I tried to read material from both sides of the debate. In my reading, I realized that many on both sides were equally convinced they were right, and were sometimes even citing the same evidence to support their conclusions.

Without realizing it, I had tripped over the central question of a branch of philosophy called epistemology: “How can we know what is true?” During my research I had read material from two different groups of scientists who came to opposite conclusions about a phenomenon. They weren’t using some incomprehensibly complex instrument, but a thermometer1, and they still couldn’t agree on what was true. How is this possible? Aren’t hard numbers and evidence enough to convince someone they are wrong, or to confirm that they are right?

The uncertainty about the search for truth is not a new one. During Jesus’ trial, Pilate asked him, “What is truth?” (John 18:38) Ironically, there is some debate as to whether Pilate was genuinely searching for truth, or if his statement was simply an irritated and indifferent reply to this troublesome Jew that he wanted rid of. Even before the time of Christ, Greek philosophers were asking these questions. For the last 2,000 years, the philosophical descendants of the Greeks in Western society have continued to struggle with certainty.

For much of human history, the denizens of the university have largely been the ones who have debated heady philosophical questions such as “What is true?” and “How can we know what is true?” However, with the rise of the printing press in the 1400s, then the explosion of electronic media in the 20th century, these questions were brought into our homes as the amount of information available to the average citizen increased more quickly than our ability to sift through it. This debate is an important one, because what we believe to be true will affect our actions.

The Rise of The Internet

From early “aughts” and into the 2010s, the Internet moved from the desktop computer at a desk in a cubbyhole off of our living rooms into our pockets. Instead of occasionally “logging in to the Internet” the Internet was now with us nearly every moment of the day and night. Before, when we had a question we would go to an encyclopedia, dictionary, or a knowledgeable friend for an answer. Now we “Google it.” Googling was easier, faster, and seemed to give us the answers we needed. With the power of the Internet in our pockets, we could answer nearly every question we could imagine in a matter of seconds. “What is the height of Mt. Everest?” “What is the protein content of chicken thighs?” “What are the side effects of long-term usage of Ibuprofen?” With these answer in hand, we could speak definitively to anyone who asked us a question, even a question we didn’t know the answer to. With Google as our research assistant, we could answer anything.

Before the Internet arrived, we relied on print books to find information. If you couldn’t find the answer in your set of encyclopedias or dictionary, you would either go to the library to find a book that could answer your question or just be okay with not knowing the answer. Today, there is no question that cannot be answered if you spend a few minutes or hours doing some online research. The Internet has made it possible for everyone to access quick answers to their every question. This has the tendency to turn us all into self-proclaimed experts. “I did my own research” is the clarion call of the informed modern man.

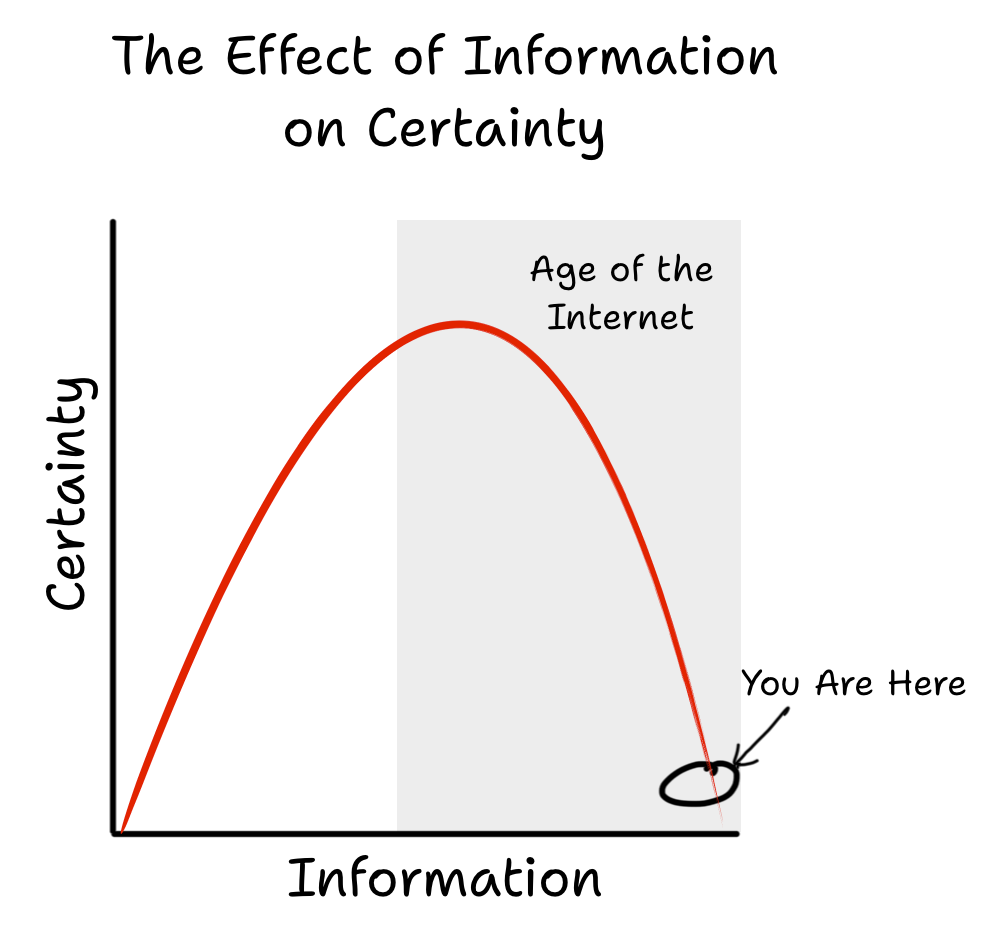

Although we now have access to more information than ever before, there is not a straight path from information to truth. In fact, as the quantity of information increases, certainty and the ability to discover what is true decreases.

The Decline of Certainty

The world is noisy. Internet brought not only an abundance of information, but a superabundance. Facts piled on top of facts until it was hard to determine which fact was correct. Jon Askonas wrote about this in the journal The New Atlantis.

Few things feel more immutable or fixed than a ball of cold, solid steel. But if you have a million of them, a strange thing happens: they will behave like a fluid, sloshing this way and that, sliding underfoot, unpredictable. In the same way and for the same reason, having a small number of facts feels like certainty and understanding; having a million feels like uncertainty and befuddlement. The facts don’t lie, but data sure does.2

From the superabundance of facts stems much of our current unsettledness. Yes, we now have question-answering machines in our pockets, but how do we sift the good and true information from the slanted, biased, and outright false? It’s like trying to listen to a concerto while surrounded by jackhammers, dump trucks, and blaring car horns—you can occasionally catch a few notes, but then the melody is swallowed in the chaos.

Much is this noise comes from many competing voices. With the Internet giving everyone a world-wide platform, there is much more for us to sift through than it was before. When I was young, my mom would refer to a thick red medical book to diagnose our sniffles and sore throats and prescribe a treatment. A mom today can now peruse the websites of the National Institute of Health, Wikipedia, Web MD, and a multitude of personal health and wellness websites and blogs. Has the access to more information given her more certainty, or has it, ironically, taken it away?

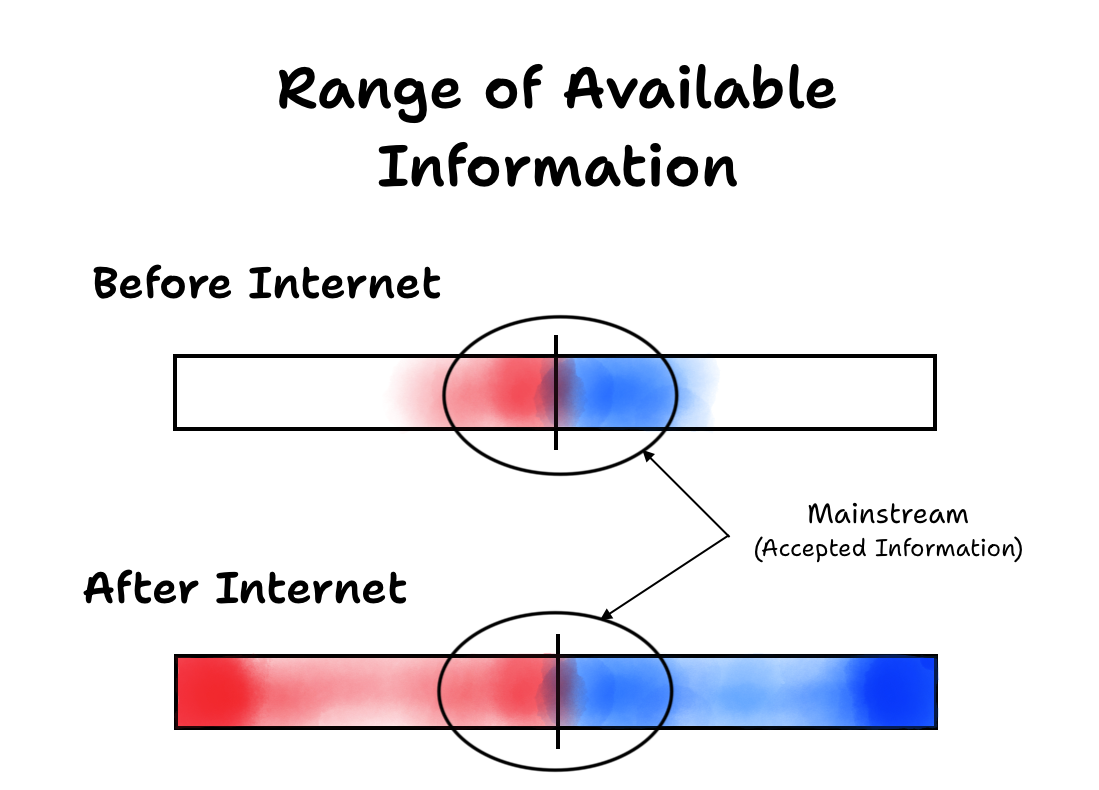

Information is messier than it used to be.Before the rise of the Internet, if you wanted to distribute your ideas and opinions to the masses, you had to go through a book publisher. If the publisher thought your ideas were kooky or not well-thought-out, they would reject your book and only a few people would likely ever read what you had to say. Publishers no doubt have rejected books that should have been printed, but with the publishing process comes a built-in error checking system that helps keep fringe and false ideas from entering the mainstream. Now, with social media platforms, blogs3, and online video, anyone with an idea, no matter how based in reality it might be, can distribute their content to thousands, or even millions, of people.

This has the effect of widening the range of information that people have access to. It might seem like more information would be better, but we are finite beings with a limited ability to absorb information and sift the true from the false. Information increases until we are awash in a sea of data with no solid land in sight.

We not only have outside pressures to deal with, we also need to deal with our own limitations and fallenness. We often fall into confirmation bias by seeking after information that confirms what we already believe. It’s all too easy to consume information that makes us feel better about our current position instead of dispassionately seeking out truth that may tell us that we are wrong. No one likes to be wrong, and so we often unconsciously do whatever we can to keep from experiencing that distress.

Many of us now get our information from online platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. The goal of these platforms is to keep you on their platform as long as possible to increase ad revenue. This is where their algorithms come in. Algorithms are pieces of computer code that watch your every move on the platform. They watch every video you watch, every article you read, and even how much time you spend on each piece of content. They then give you more of what you seem to like to keep you online as long as possible.

The algorithms then keep serving you tasty platters of content crafted specifically for your interests and proclivities. This has the effect of creating echo chambers where the only content and discussion that you see is that which already agrees with what you think instead of showing you a competing viewpoint or piece of evidence that you should weigh before you make a decision.

These algorithms also feed more extreme positions and opinions. Ideas that are controversial or fringe tend to get more attention, which drives more viewers or readers, which then incentivizes the people posting the content to make their views yet even more radical to attract viewers. This creates a reinforcing cycle that strengthens the extremes while weakening the mainstream and moderate positions.

What is the effect of everyone having a world-wide platform and being able to speak with authority on any subject they choose? The mainstream is swept away, and what is left is a muddy swirl of opinions, hot takes, and personal anecdotes. With both the proliferation of information and the widening the range of perspectives that are available, we often aren’t sure who or what to trust.

This essay will continue in a Part 2 sometime in the next several weeks.

- To be clear, these thermometers are not your average alcohol bulb thermometer, and might even be orbiting in space, but they are still just measuring temperature. ↩

- https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/what-was-the-fact ↩

- Don’t worry, I see the irony of posting this essay on my personal blog. ↩

Leave a reply to The Fall of Authorities – Invisible Things Cancel reply